Last updated:

What is special about the Kindergarten in Auroville ?

A comparative study of childhood education in Montessori, Waldorf, Progressive Schools and Auroville by Heidi Watts, Ph.D., Director, Education, Antioch University

From a brochure published by SAIIER in May 2000

Everyone has in him something divine, something his own, a chance of perfection and strength in however small a sphere which God offers him to take or refuse. The chief aim of education should be to help the growing soul to draw out that in itself which is best and make it perfect for a noble use.

- Sri Aurobindo

Introduction

A friend in Auroville said to me recently, “What’s the kindergarten like?”, and I said, “It’s a very special place.” “Really?”, she said. “Why? What happens there?” This essay is an attempt to answer her questions, and similar questions which my friends and acquaintances in and out of Auroville have asked from time to time.

I met with the staff of the Auroville Kindergarten in December 1996, and we asked ourselves some related questions. What is special and what is unique about the kindergarten in Auroville? How is it like other kindergartens and how is it different? What is developmentally appropriate for children at this age?

Is the kindergarten programme consistent with what is

known about the developing needs of young children? Does it have a coherent philosophy?

To provide a background to the discussion at our first meeting I reviewed three compatible approaches to kindergarten instruction: Montessori, Waldorf and the Progressive movement. At our second meeting we reviewed developmental patterns of growth based on a book by Chip Wood called Yardsticks. In this essay

I want to recapitulate our conversations and describe my impressions, as an outsider, about what is special in this kindergarten. But first I want to respond to my friend’s second question: What happens there? My hope is that by describing a day in the kindergarten you can visualize the people, the space and the atmosphere as you read on.

The Auroville Kindergarten

How to describe the Auroville Kindergarten? There are approximately 46 children in four groups. The Yellow Group is composed of three years old, the Orange Group of four year olds, the Blue Group of five year olds and the Green Group of six year olds. In every class, of course, there are some children who are just coming up to a birthday either at the early end of the age group or the latter end. For each group there is a main teacher and an assistant. In all the groups, the teachers come originally from France, Germany, Italy and India. The cultural mix of children is even more varied. They are all children of Aurovilians, but the languages spoken at home may range from Tamil to Russian, French to Hindi. The common language for all these groups, and the language of instruction in the kindergarten, is English.

The place

The kindergarten is housed in a new building, designed to their specifications, and is located in the city area. It is a large, airy, one story building, with four classrooms, a dining room, a library, a children’s toilet room and a large open activity area opening off a central, circular entrance cum assembly hall. The building is of warm red sand brick with deep window seats and accents of wood, like the classroom doors, painted in bright colours. Behind the orange door you will find the Orange Group, and so on.

In the inviting circular central space one wall is devoted to a large bulletin board where volunteers have arranged that week an attractive display to illustrate the concept of wind. On another wall there is a very large aquarium at child’s eye level where fish float dreamily amongst the underwater ferns. Sometimes there will be a display of children’s work on another wall. At the moment a frieze of elephants march around the base board, crayoned like elephants who have walked through rainbows.

The physical activity and energy needs of young children are well accommodated. The large activity room sometimes has a dance or movement class, otherwise children may be in there playing their own games. The playground, in the back of the building, has swings and a large climbing apparatus. There is a washing area and a large contained outdoor sand area for sand play. A swimming pool provides opportunities for welcome relief as the days grow hotter. Flowers and small child planted gardens surround the buildings.

It is truly a kinder-garten, a children’s garden.

The programme

The children, not quite old enough to cycle by themselves, come by bus and parent transport, straggling in between 8:00 and 8:30. At 8:30 or a little after, each class gathers for an opening circle, to share stories, to do an activity together. Each circle begins with a small ritual. The children sit on the floor in a circle, light a candle, close their eyes, and meditate quietly for a few minutes. This is “concentration”, a uniquely Aurovilian practice which is used to start and sometimes conclude meetings, classes, talks, etc. When observed in schools it has a wonderfully calming and centreing effect, even on the most active children.

After the opening circle there is time for talking and sharing, and for planned activities. At 10:30 there is a snack and short recess, then lunch, served in an adjoining dining space, arrives at 12:00. After lunch children play until it is time to leave around one o’clock. The kindergarten curriculum has been described by the staff in some detail and I would like to reproduce some of that description here, organized by the five domains of the personality identified by The Mother as the physical, the mental, the vital, the psychic and the spiritual.

The psychic and spiritual being

- The atmosphere in the school is warm and loving, simple and beautiful. The children feel very secure and at ease and experience in their own way that the place is there for them, to meet their needs.

- The whole school often chooses to follow one topic together at the same time, which brings about a sense of sharing and oneness.

- A natural friendship develops between children of different cultures and nationalities thereby promoting a sense of human unity.

- Each morning there is a basket of flowers with which to make a kolam, a traditional Tamil flower design, in the centre of the entrance hall. Children spontaneously start making the kolam or help a teacher in doing so. Allowing children to play with flowers brings out a special sensitivity in them.

- All the teachers get a chance to interact with all the children at some point during the day or the week.

- This helps to create a sense of wholeness and integration in the relationships between teachers and children, with the result that no sharp break occurs when they move from one group to another.

- Each group visits the homes of all the children in the group. This narrows the gap between home and school and helps the children know each other and make friends more easily. The emotional climate of the class improves greatly.

- Teachers are alert in observing the children and periodically share their observations among themselves and with the parents, in order to foster greater consciousness of the uniqueness of each child. Teachers have found that as they learn more about the unique characteristics of each child they are better able to help that child’s growth.

- A subtle balance is maintained between leading the children into teacher-directed activities and leaving the children free to choose between a set of activities offered to them.

The physical being

Sri Aurobindo and The Mother have underlined the importance of physical culture, the ultimate aim of which is to infuse a higher consciousness into the cells of our bodies. Mother said, “If we cultivate the body by clear sighted and rational methods, at the same time we are helping the growth of the soul, its progress and enlightenment.”

At the kindergarten the following physical activities take place.

- For about twenty minutes after snack in the middle of the morning the children are free to play in the playground, where there are slides, swings, a see-saw and a set of tunnels along a raised passage. While they are under observation, teachers leave them completely free to play together in groups or singly. Qualities of leadership and acting in concert develop spontaneously.

- The children are taken to an adjacent playground where they practice walking on a pipe, crossing a monkey-bridge both from on top and while hanging, somersaulting on a raised bar at different heights, and climbing on a chain wall. In their last year at the school they also learn to skip and play many children’s games like tug-o-war.

- Periodically a dance teacher works with the children doing movements presented as games and simple exercises, which often leads to a marked change in their body consciousness.

- Two teachers lead the children in body awareness work once a week from their second year in kindergarten. The exercises and games encourage concentration and lead the children to awareness of all parts of the body.

- The children also go to the swimming pool at least twice a week and learn through games many exercises that are preliminary to learning to swim.

The vital being

Sri Aurobindo and The Mother have pointed out the fact that training for the vital in the personality is presently carried out unscientifically, if at all. They have put particular emphasis on developing and training the responses of our sense-organs to be exact and precise as a preliminary to the discovery of the inner sense. Importance has been given to developing the aesthetic sense, the sense of beauty, harmony and order. The emotional personality can be easily distorted if proper conditions are not created for a child’s growth.

In the turbulence of modern life many emotional problems show up in children. Some of the practices in the kindergarten to cultivate the vital being are:

- A set of simple habits is insisted upon gently until they come naturally to the children.

- When coming into the building they are expected to arrange their sandals in an orderly line. If they use any book or game they are expected to put it back in place; neatness in all work is expected as well as not interrupting an adult or another child; eating without making a mess; washing hands before and after eating; brushing teeth after lunch and rinsing the mouth after a snack. Children are encouraged to at least try all the food items offered. Here the teachers do not force but gently insist if they see a child rejecting food out of caprice and not from innate revulsion.

- An important though difficult area is the interactions among the children themselves.

- Being mean to another, aiming nasty remarks, not sharing, violence, and playing favourites are all behaviours which appear in some of the children from time to time. Teachers watch the children closely and find appropriate forms of conflict resolution to deal with these tendencies when they appear. One of the responses, for instance, is to separate the fighters, get down at eye level with them, and make each explain the what and why of the conflict. The attempt is not to suppress the energy of the children but to redirect it in a positive way. The children are never judged “bad”; it is only the specific behaviour which is unacceptable.

- There are many opportunities for free creative and expressive activities such as big blocks, Lego, drawing, painting and drama. Simple dramatic exercises help the children to sharpen their sensory responses, encourage the development of the imagination, and increase consciousness of the vital being. Acting out different emotional states such as anger or fear fosters the capacity to create distance between the self and the emotions, and with that the ability to have greater control over the emotions.

- Games to develop the sensory faculties are regularly introduced. Good games are commercially available for training the vision, but we have developed many other simple games using common objects such as fruits and seeds to strengthen the perception of the other senses.

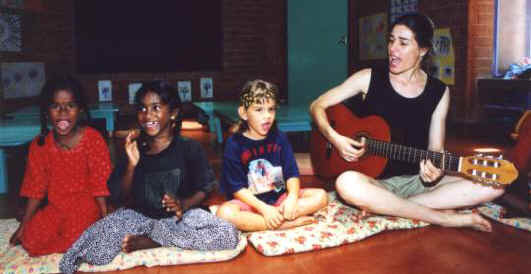

- The children learn many songs in English Tamil, French and Sanskrit, and the oldest group begins to learn musical notation.

- Many children, particularly from separated parents, show a lack of self-esteem. The staff pay special attention to these children and take care that other children do not use put-down statements to them.

- Competitiveness can be strong in some children

- and often adversely affects the whole group. The staff tries to identify the causes and find appropriate ways to work with them. They encourage an understanding that children are not all good at the same thing - some are good at sports, others at painting, or music, and so on - and play many games which have no competitive elements to foster cooperation.

The mental being

Mother said that as a general rule, before the age of seven, the child is not conscious of himself or herself and doesn’t know why he or she does things: “that is the time to cultivate his attention, teach him to concentrate on what he does, give him a minimum of knowledge sufficient for him not to be like a little animal, but to belong to the human race through an elementary intellectual development”.

She also said, “Understand and see clearly why this movement took place, why that impulse, what the child’s inner constitution is, which point needs to be strengthened and brought to the fore. That’s all you have to do, and then leave them: leave them free to blossom, just give them the opportunity to see many things, touch many things, do as many things as possible. It’s great fun. And above all, do not try to impose on them something you think you know.”

- There is no stress on abstract mental reasoning in the kindergarten. Everything is concrete and tangible. The children are exposed to and invited to be conscious of the world around them. They take many trips to the farms, beaches, forests, canyons and lakes in and around Auroville. The children learn to appreciate nature and its diversity from their experience in it.

- As part of the nature study many animals and birds are brought into the school: turtles, snakes, lizards and other common species are brought to school so that children can learn the proper way of handling them.

- The children do simple cooking and gardening activities. They celebrate the holidays of Christmas, Ganesh Chaturthi, Deepavali, and also the birthdays of Sri Aurobindo and Mother.

- At the kindergarten the children are exposed to four languages: English, Tamil, French and Sanskrit. English is the medium of instruction and they learn simple songs, numbers and words in the other languages. Children of this age are particularly receptive to the sounds of other languages; if they learn to reproduce those sounds when their vocal organs are most plastic they can come to fluency more readily when they are older.

- All children are involved in the sensory activities which provide a strong foundation for the later development of reading and writing skills.

- As individuals show their developmental readiness they are encouraged to do more with reading and writing.

- In the younger groups mathematical concepts are introduced through sorting, grouping, algorithms, comparisons, manipulating numbers from 0 to 12, always apprehending with the body as well as with the mind. The older children learn mathematical concepts through games, working with numbers up to 50, with simple addition, subtraction and occasionally even multiplication and division. An understanding of weight, volume, time and area is developed through the use of games and simple but appropriate materials.

Through conscious attention to the psychic and spiritual being, physical culture, education for the vital, and an emphasis on experiential learning rather than on abstract thinking, the kindergarten is consistent throughout as an example of integral education for young children.

Balance

It is easier to describe the place and the programme than to describe the feeling which permeates the kindergarten. “Balance” is the word I heard myself saying to my friend. Balance. There is a strong but subtle balance between meeting the needs of the individual child and meeting the needs of the group. Children have many opportunities for self-expression, and for the exploration of their own interests, but they are also expected to be respectful and considerate toward each other, to act without license in the environment, to listen, to contribute and to share.

There is a similar balance in the rhythm of the day which alternates between vigorous activity and quiet activity, directed activity and free choice activities.

A somewhat unusual aspect of the kindergarten curriculum is the emphasis on observation and concentration, developing the senses in different ways. The physical, vital, intuitive, social, and spiritual aspects of the growing child each have a place for play (which is the work of children) in this kindergarten. This is completely consistent with the aim of the kindergarten, which is to nurture the child’s growth in all aspects and toward the divine consciousness. I have seen kindergartens which excel in their focus on social development, or on cognitive skills, but rarely a kindergarten which achieves a balance between all the aspects of the growing child, including the psychic and the spiritual.

One of the specific features of the kindergarten which I found admirable is the body work in movement which Joan and Aloka are doing in all the Aurovilian schools. I surprise myself at how readily the superlatives come to mind when I see their work. From the youngest to the oldest children they have developed exercises and activities which draw out and strengthen the non-verbal qualities in the developing child. And they do it all with what seems an intuitive sense of timing, of building from one small accomplishment to the next and the next, in ascending levels of difficulty. Children become conscious of their bodies, of where they are in space, of how they move, and of where their centre of gravity is, by many different activities. They may experiment with walking in different ways, fast, slow, dragging, skipping, walking on a line, walking on a plank, walking up and down over a series of obstacles, walking up

a ladder, walking blindfolded, walking to music; each time I am there it is something different, and yet each time I can see the connection between activities and the increasing competence and self-confidence in the children.

Joan and Aloka have combined their backgrounds in dance and physical therapy and created a synthesis which addresses the developing physical skills of the growing child. Here, I think, the word unique may properly be applied. I have never seen such care and concentration in movement among children in other schools. I have seen a similar understanding and control of the body sometimes in dance and gymnastics classes, but never across the board with all the children who happen to be in the school. (Note: the Body Awareness work is described in more detail in SAIIER’s Research Letter #2 for 1997-98.)

Their achievement may be aided by the fact that Auroville children are raised in an active environment. They cycle and walk for the most part to get around,

and generally have a great deal of freedom in movement both within the house and without. There is an emphasis on sports and healthy outdoor activities, and Auroville is a relatively safe place for children; they may roam freely, and often do.

Another admirable feature of the kindergarten is the respect for language differences. All children learn to speak in English, but they also have classes in French, Tamil and Sanskrit where they learn songs, games and simple phrases, enough to begin learning how to form the sounds of the language when they are at the optimal age for hearing, reproducing and remembering linguistic sounds.

Although this is a rather brisk tour through the kindergarten, I hope it will provide enough of a guide for readers unfamiliar with the kindergarten programme to assist them in making comparisons during the philosophical overview which follows.

Philosophical assumptions determine nature of the school

In our first seminar we talked about the differences between different compatible approaches to kindergarten, and to set the stage reviewed briefly the philosophical foundations for these approaches. Any real understanding of an educational philosophy must go back to very basic assumptions about the nature of humankind, the universe, and the purpose of life as we know it. Why are we on this earth? What is the nature of human beings? Are we born inherently good, inherently evil, or morally neutral? What is the relationship between human beings and the Divine? The answers we give to these basic philosophical questions shape the answers we give to questions about the aim and form of education.

If one believes, as the Calvinists did, that children are born in original sin, and have an inherent disposition to evil, then the task of education becomes training or requiring the child to be good, against his or her natural inclinations.

If one believes that humans are born inherently good, as Rousseau did, then the task of education is primarily to see that the natural inclinations of the child are not curtailed and that the restrictions of personal freedom necessary for living in a society are kept to a minimum.

If one believes with Dewey that children are born neither good nor bad but learn right and wrong from their interaction with the environment in which they grow, then the nature of the environment, which means also the people and the experiences of the child’s life, are of great importance.

These greatly oversimplified statements are offered only to show that even the most practical decisions in schools are ultimately governed by the assumptions we make about the nature of the universe. Having said this I hasten to add that no school is a perfect exemplification of one philosophy, since even within the “purest” schools there are small variations in personal beliefs, and, yet more likely, in the way in which similar beliefs are executed. So, for example, even though we all believe that freedom of expression is essential for children, one person’s way of encouraging freedom of expression for the child may look quite different from the way it looks to another person.

In a little book called Issues and Alternatives in Educational Philosophy George Knight suggests one way to understand how different assumptions may be reflected in practice. He examines each philosophical school of education in four categories: the role of the teacher, the role of the student, the role of the curriculum, and the aim of education. As an example, in schools of the traditional or Calvinist approach, operating on the assumption that children if left to their own devices will grow up as little savages, The Lord of the Flies is a good example of this philosophy. The role of the teacher is to direct students in the right ways to think and behave, and the role of the student is to be obedient, respectful and industrious. The curriculum should be composed of basic skills, instruction in values, and training for the mind.

In “free schools”, where the founders believe that children, left to themselves, will flourish and turn naturally toward what is good and true, the role of the teacher is to facilitate, to stand aside, and to intervene only when necessary. A.S. Neill, head of Summerhill, one of the most famous free schools, said that at Summerhill there were only two rules: you could not do anything which would hurt someone else, and you could not do anything which would hurt yourself. Of course there is a wide space for disagreement there over what constitutes “hurt”, but in general Neill intervened only when the injury was likely to be physical and long lasting, either to the person or the environment i.e. you could not burn down a building or throw rocks at a passer-by, but you could spend all day building a tree fort and never go to class, and you could eat/sleep/work whenever you wanted. Neill argued that after a period of experimentation children would naturally establish healthy patterns of work and play. The role of the student is to develop his or her own potential without interference.

When Sri Aurobindo said “Mind must be consulted in its own growth”, I believe the word “consulted” indicates that the children must participate in decisions about their own learning, but it does not mean they should be left to their own devices. At the kindergarten seminar we positioned ourselves somewhere in the middle between these extremes, though with perhaps more sympathy for the latter than the former, and looked at three contemporary approaches to early childhood education which seemed most likely to fit within our own belief system and which might be instructive for this kindergarten programme.

Three philosophically compatible approaches

The three approaches - Montessori, Waldorf and the Progressive movement - have several significant features in common. All three value the uniqueness and integrity of the child as a person, and of childhood as a state of being. All three value the child as a whole person, one with developing abilities in the physical, the social, the mental and the emotional realms. (One distinguishing difference between these generally compatible approaches is the difference in emphasis on the spiritual and intuitive faculties of the child, a topic I will address later.) All three believe that the child grows through active engagement with the environment, and that the role of the adult as mentor and model can not be overstated.

Finally, all three approaches are consistent with developmental stage theory, even though their founders could not have been acquainted with the explosion of research into children’s thinking which has characterized the last sixty years. Certainly they are all one in seeing childhood as unique, and as a period of exceptionally rapid growth in all the domains.

Montessori Schools

Maria Montessori was born in Italy, and after training as a teacher and psychologist she was chosen, in 1906, to establish schools for the tenement children in one of Italy’s worst slums. These “children’s houses” were part of a “scientific experiment” on behalf of children. The method and materials piloted there are now famous around the world, and there are Montessori schools on every continent.

Montessori said “the aim of education is life itself, not preparation for life”. She felt it was imperative that a school allow a child to develop naturally, but not with undisciplined freedom, and she saw the role of the environment as critical in directing the natural development of the child. In Montessori schools the role of the teacher is that of guide, observer, coach, facilitator and overall manager. The Montessori teacher does little explicit teaching, but must be very observant, watching the children as they work with the materials, guiding them when they are confused, making sure the sequence is appropriate, preparing the classroom, and organizing the activities.

Perhaps because she began working initially with slum children living in squalor, Montessori stressed the importance of cleanliness and good health habits.

As a part of the curriculum, all children participate in cleaning the classroom, setting out the meals, and cleaning up afterwards. They learn to wash their hands and brush their teeth. In the play areas there are little wash tubs, ironing boards and housekeeping equipment for the children to learn domestic skills through play.

Another emphasis in Montessori schools is on the development of sensory awareness. Children are taught through all the senses, with a special emphasis on the kinesthetic, and the curriculum encourages consciousness of the senses through the use of specially prepared materials. Montessori materials are famous around the world, and the concept of using materials to teach specific skills and concepts has spread with the materials. There are graduated cylinders to teach an understanding of shapes and graduated sizes, vials for sniffing, closed containers for sound discrimination, sandpaper letters to teach the form of the letters through the fingers, and much more. The aesthetic sense of the child is nurtured by the pleasing quality of the classroom and the materials, which are clean, orderly, simple, and beautifully conceived. Although the teacher may need to manage behaviour at first, the aim and expectation is always that discipline should come from within.

In a Montessori school the role of the teacher is essential but discreet; the role of the environment as an educational tool is of prime importance; the role of the child is to be active in exploration and expression within the educational environment, and tidy and considerate in behaviour. Perhaps it would be helpful to note that this description is drawn from my experience with Montessori schools in the U.S. and through reading. Actual Montessori schools in India and elsewhere may have evolved in directions which no longer exactly match this description.

Waldorf Schools

It is interesting that the Waldorf school movement began in a way similar to that of the Montessori movement. Rudolf Steiner, a German educator and philosopher, was asked to start a school for the children of the workers in a Waldorf factory in Stuttgart. Steiner was born in Germany in 1861. He described a school of philosophy known as Anthroposophy: the wisdom of the human being. Anthroposophy, though oriented toward the Christian faith, is primarily concerned with the acknowledgement and development of spirituality in the person and the universe. The Waldorf movement is the fastest growing private school movement in the world today.

One of the most interesting features of the Waldorf School is the structure: teachers stay with their classes from first grade through 8th. Obviously a class becomes very much like a family; less obviously the challenge for the teacher is to master all the subjects in the elementary curriculum. As Torin Finser admirably illustrates in School as a Journey, his account of teaching for eight years in a Waldorf school, the teacher also comes to know from personal experience the extraordinary developmental changes which take place in children during those formative years.

In the Waldorf schools every effort has been made to make the overall plan for the curriculum fit the evolving interests of children. So in the kindergarten, a time of rich fantasy life, fairies, elves and goblins appears in the teacher’s stories and the children’s play; at sixth grade when children are beginning to venture out on foot and cycle to explore the world around them, explorers become the focus of the curriculum. There are many such examples.

As with Montessori, all of the senses are cultivated and engaged, but in Waldorf schools this is done primarily through art, ritual, song and movement. Math is taught with rhythms and movement. Children learn to recite chants and verses. The teacher greets each child at the door with a handshake, and inevitably there will be another small ritual around snack or lunch. There are festivals at set times of the year: a Christmas pageant, a Maypole dance. The environment is carefully structured so that it is aesthetically pleasing, soft, harmonious, and not overly stimulating. Pastel colours and swirling shapes are common in Waldorf drawings, and only natural materials such as wooden toys and beeswax crayons are used.

Unlike Montessori schools or the schools within the Progressive tradition, Waldorf schools are teacher centred. They are not oppressive; great care and respect is accorded the children, but the curriculum is determined by the teacher within the prescribed Waldorf traditions. Materials, festivals, and the sequence of activities are teacher directed. All ten year olds will study Norse myths; ancient cultures and attention to the Maypole dance are essential in every fifth grade class. Each of these curricular selections has a rationale rooted in Steiner’s understanding of the developing interests of the child, and are often inspired, in my opinion, but also absolute. There is little room for deviation.

Waldorf teachers believe young children need to be directed in their expressive efforts so that later they will be better able to create their own work. In a Montessori school the materials and the curricular expectations guide the children, but the children have more choice in the selection of activities and the means of expression. In the student centred progressive schools the environment will be “messier”; children will be presented with a wide variety of materials to work with, particularly openhanded materials which they may bend to their own discoveries; and they will be encouraged to make their own choices in materials and activities.

Progressive Schools

Progressive schools are more difficult to describe, because “Progressive” is a general set of characteristics, suggesting a basic orientation to the world which extends far beyond schooling, into politics, economics, labour relations, human rights and the arts. Montessori schools, for example, fall within the broad definition of progressive education. Montessori and Waldorf schools, being in the private domain, may exercise some authority over the schools which bear their name to keep them within the accepted practices of the approach. Not so progressive schools. Some progressive schools are private schools, and those like The City and Country School in NY, or Mirrambika in Delhi, are relatively “pure” manifestations of the philosophy, but there are progressive teachers in non-progressive schools and non-progressive teachers in progressive schools, and some aspects of progressive practice have changed from being revolutionary to being common place in American and British schools. On the political football field of American education today, “progressive” has been misinterpreted to mean something like the free school movement I described above in its most chaotic and unruly manifestations, in contrast to a “back to basics” movement with its emphasis on facts, drill and examinations.

Consequently, to avoid the aversive associations with the label “progressive”, some schools firmly within that tradition identify themselves with other names, such as the open classroom, integrated day, constructivist, or student centred.

John Dewey, the great American educational philosopher, and the man most closely associated with the concept of progressivism in education, strongly repudiated the free school interpretation of progressivism in one of his last works, a little book called Experience and Education. Dewey believed that children are born neutral, that healthy development is the aim of education, that we all learn and grow from interaction within the environment - which includes people as well as things, that in fact all that we learn comes from experience; but it is not experience alone, it is the meaning we make of it which directs our perceptions and our actions. Out of these beliefs Dewey postulated a curriculum which must begin with what is relevant, what matters to the child, but which continually draws us on. As Sri Aurobindo said, teaching must be from the near to the far. Humans are curious creatures, and through our explorations we learn more and more about the world and about ourselves. One of the goals of education must surely be to cultivate the spirit of enquiry so that education never ends.

Auroville Schools/Education

Where does the Auroville Kindergarten fit in this medley of approaches? The kindergarten seems to me to be a true exemplification of the progressive approach.

It is student centred; experiences are carefully constructed to be relevant, developmentally appropriate and educative; the whole child is addressed; there are many opportunities for choice but not license; and children learn from an active engagement with the environment. On the other hand, the emphasis in observation, concentration and the development of the senses reminds me of a Montessori school, and the attention to the spiritual climate of the school, with rituals and the awareness of the presence of Sri Aurobindo and Mother remind me of the Waldorf schools I have seen. In each of the approaches I have described there is much of value. What we take from them depends in part on our own philosophical inclinations and our own intuitive sense of what is right for these children in this place.

The Auroville Kindergarten resonates with the three simple but profound principles enunciated by Sri Aurobindo: “Nothing can be taught. Work from the near to the far. Mind must be consulted in its own growth. “Children learn by doing, not by “being taught”. All activities begin with the known and the concrete before moving to new forms and structures. Children are presented with appropriate choices, and encouraged to solve their own problems. Mother said, “To love to learn is the most precious gift that one can make to a child: to love to learn always and everywhere.” In this kindergarten children love to learn.

Some of the unique features of this kindergarten, features which may distinguish it from each of the other educational movements with a compatible philosophy, have been described: the emphasis on observation and concentration, the development of sensory and body awareness, the cultivation of all five domains of the being including a direct address to the vital, psychic and spiritual domains, the attention to early language development, and the integrity of the environment.

The purpose of education in Auroville is, in the words of Sri Aurobindo, to help the growing soul draw out the best in itself: “Everyone has in him something divine, something his own, a chance of perfection and strength in however small a sphere which God offers him to take or refuse. The chief aim of education should be to help the growing soul to draw out that in itself which is best and make it perfect for a noble use.”

Chapter 3

Schools for young children must be developmentally appropriate

Developmental stage theory, a relatively new branch of psychology, assumes that in their growth from infancy to adulthood humans go through stages which are sequential, invariant and universal. These stages apply to growth in all domains: the physical, the mental (or cognitive), the vital (or affective) and the social. Some developmental psychologists have also posited moral and spiritual stages of development. Although the stages reflect a universal pattern for growth, human beings pass through these stages at different rates and with varying degrees of sophistication. One person may advance rapidly in social skills but be slow to develop physically, another may spurt ahead in the cognitive domain but learn social skills slowly. In a broad sense, however, it is not possible to jump a stage, or to be force-marched through it. Until a child is ready to make growth in a given domain and through a given stage, all that loving parents and conscientious teachers can do is to prepare the environment; we can not “make” growth happen. Patterns of development are also strongly affected by the individual personality with which we come into the world, and with the conditions of the culture in which we live. Children brought up in a seafaring society may learn to swim very early; children brought up by highly verbal parents are apt to begin talking earlier.

Unlike the concept of childhood which was common a century ago, and still prevails in some societies, children are not thought of or treated like little adults. Childhood is recognized as a stage in human development with special qualities all its own. Psychological theory, supported by our own common sense observations of children, shows us that young children do not think like adults; they do not even think like older children. Their perceptions of the world are embedded in their own spontaneous actions and desires. They do not reason abstractly; they do not even reason logically as we understand logic, though within the range of their perceptions the thinking may be very logical. Ask your four year old whether he has a brother or sister. If he says yes, ask him who is the sister/brother of that person? It is not often that the four year old understands that the relationship is reciprocal; that if Jack is his brother he is also Jack’s brother. Ask him what happens to the sun at night. But don’t try to force him to learn the right answer because he does not yet have enough experience of the world, or the mental ability, to understand abstractly that the earth is moving when you can just look around and see that it isn’t. Even I have a little trouble with that idea when I think about it! No wonder the flat earth theory took so long to be disproved. The young child knows the world as he or she sees it - literally. That things may be other than they seem is a stage of thinking they will come to later.

At one of our kindergarten seminars we discussed guidelines for development in young children from the book Yardsticks: Children in the Classroom Ages 2-12 in which Chip Wood, drawing on the theoretical work of Arnold Gesell, Piaget and others, as well as on his own extensive experience with children, has described the common characteristics of children at each age from four to twelve. He describes these common characteristics in four domains: the physical, the cognitive (mental), the social, and in the realm of language. Within the physical domain he notes rapid changes in vision, with fine and gross motor ability as the child matures. For example, in four year olds vision and fine motor ability are still developing, and it is therefore unwise to expect the child to do close visual work, like copying from the board, or fine motor activity like embroidery. Six year olds, on the other hand, have gained increasing body control and are mentally ready for more abstract tasks - getting ready to be readers and writers as well as runners and singers.

Four year olds, he says, are “ready for everything”. They are explorers, adventurers, sparkling with energy, continuously on the move, full of exaggeration, using and enjoying many large muscle activities, if not yet ready for fine motor and close-up visual activity. Fives are more compliant and more comfortable, but they are also happier when the environment is structured and predictable, with bounded opportunities for exploration and free play. Sixes are “in an age of dramatic physical, cognitive and social change”. They are industrious, they thrive on praise, they can be extremist in anything, and they are at the threshold of large changes in their perceptions of the world.

In general the young child is egocentric and impulsive. He knows only the world immediately around him, and, embedded in his perceptions, he is clear about what he thinks he knows, he is also full of curiosity; he questions, he investigates, he expects the world to bend to his desires, and he is seldom capable of planning ahead.

(This is a very skimpy summary of a very readable book. Parents and teachers of children up to the age of 12 may be interested in borrowing it from the Teacher’s Access Centre at Transition. All of the other books mentioned are also available to borrow.)

As we looked at the defining characteristics of children at different levels of development we tried to match their needs and interests with the curriculum of the kindergarten, and for the most part found the curriculum a fitting mix for the changing developmental patterns of four to six year olds.

Conclusion

The kindergarten is not perfect, of course.

In our discussions we found areas where the teachers would like to make small changes, or areas they want to explore further, and, as we all know, it takes a lot of hard running just to stay in place. There is no reason for complacency; a balance implies that there may always be imbalance tomorrow, or at any minute. Balance takes concentration on the goal, continuous self-reflection, and subtle adjustments of tension simply to remain as one is.

I have seen a videotape of some of the work of Joan and Aloka with the children. In these scenes the children move with amazing concentration and balance up a ladder and down a ladder, balancing a tin plate on the point of a pencil. They move gracefully and with total concentration. They move together. Sometimes one child transfers the balancing plate to another without dropping it or losing the posture, sometimes not.

As I watched the videotape I thought of the kindergarten balance. It is true that not all children are well-centred all the time. It is true that sometimes the parts do not weave perfectly into each other. Nonetheless the coming together excites our admiration. I have had that feeling about the kindergarten.

The kindergarten is not perfect, but it is a very special place.

Without detracting from the specialness of the kindergarten I should also say that kindergartens in general are easier to manage for several reasons. Children at this age are extremely open and plastic, hungry for learning; they have not yet had aversive school experiences to “turn them off”; parents and the larger society have fewer external expectations. We do not expect kindergarten children to pass examinations, and although the pressure to prepare for some higher form of schooling exists it is not strident. There is more unanimity among parents and the community about what a kindergarten should provide than at any other level of education.

However, these observations are not intended to minimize what is happening with these young children. They may be learning faster than they will ever learn again. Daily their vocabulary expands, and not just in one language but in two or three. Every day they are learning and practicing social skills, and, like the mind, the young bodies are developing new capacities.

There is a much quoted book in the U.S. entitled, Everything I Ever Really Needed to Know I Learned in Kindergarten, in which the author describes how in kindergarten he learned to listen, to speak, to clean up, to share, to express himself, to ask good questions, to trust and be trusted. Auroville children would know what he means.

References

- Dewey, John. (1938) Experience and Education. Macmillan. NY

- Finser, Torin. (1994) School as a journey. Anthroposophic Press. NY

- Fulgrum, Robert. Everything I Ever Really Needed to Know I Learned in kindergarten.

- Knight, George. (1989) Issues and Alternatives in Educational Philosophy. Andrews University Press. Michigan

- Montessori, Maria. (1967) The Discovery of the Child. Ballantine Books. NY

- Pratt, Caroline. (1948) 1 Learn from Children. Simon and Shuster. NY

- Sri Aurobindo and The Mother. On Education.

- Wood, Chip.(1994) Yardsticks: Children in the Classroom Ages 2-12. Northeast Foundation for Children. Pittsfield, MA

-

Nandanam kindergarten for children between 2.5 to 7 years of age

-

Deepanam School for children of 6 to 14 years of age

-

'The play of painting" at the Auroville Kindergarten

-

Kindergarten for children from 2.5 to 7 years of age

-

New Era Secondary School (NESS) - A CBSE Affiliated School

-

Transition school for children of 6 - 14 years

-

Future School for children of 14 - 19 years

-

Aha! Kindergarten for children of 2.5 to 7 years age